I’m not sure how I became a record collector. Back in the day, I didn’t have two sticks to rub together. When I moved to Boston, I fit everything in a Renault 8, which promptly died on the Fenway and disappeared from my life. But the seeds of the disease were there. I had a Sony TC-355 tape recorder that I had used all through high school to make recordings of my pieces, pieces I liked, the records of friends, and the occasional bootleg of a live show. I still have the recorder, and though it no longer records, it will still play a tape. I still have its predecessor also, an Aiwa TP-802. And the tapes recorded on it, for the most part. It is exactly as functional as the Sony. This might seem like a digression, but it is the same song transposed. That essence is the hanging on to of old stuff, the keeping of it alive. I had tapes, but they did not travel as a collection, to Boston. They remained in my childhood home at 1612 Moffet Road in Silver Spring, Maryland. That went for the phonograph records, also. The turntable, the AR-XA, purchased with Washington Post paper route money at Dixie Hi-Fi in Kensington, Maryland, did go to Boston. In fact, it also was at East Denis on Cape Cod, where it suffered the ministrations of Lewis Lane, who used some sort of mucilage to glue a penny to the tone arm. Speaking of notable collectors, Lewis had amassed so many shellac records that his ceiling bowed under the weight. Which brings up an important note about collectors: you can’t take it with you. After Lewis died, I head from Wilfred Churchill, my piano teacher at the Conservatory, that the records had been stored too long in that attic on the Cape, where they’d been eaten by the salty air and vermin.

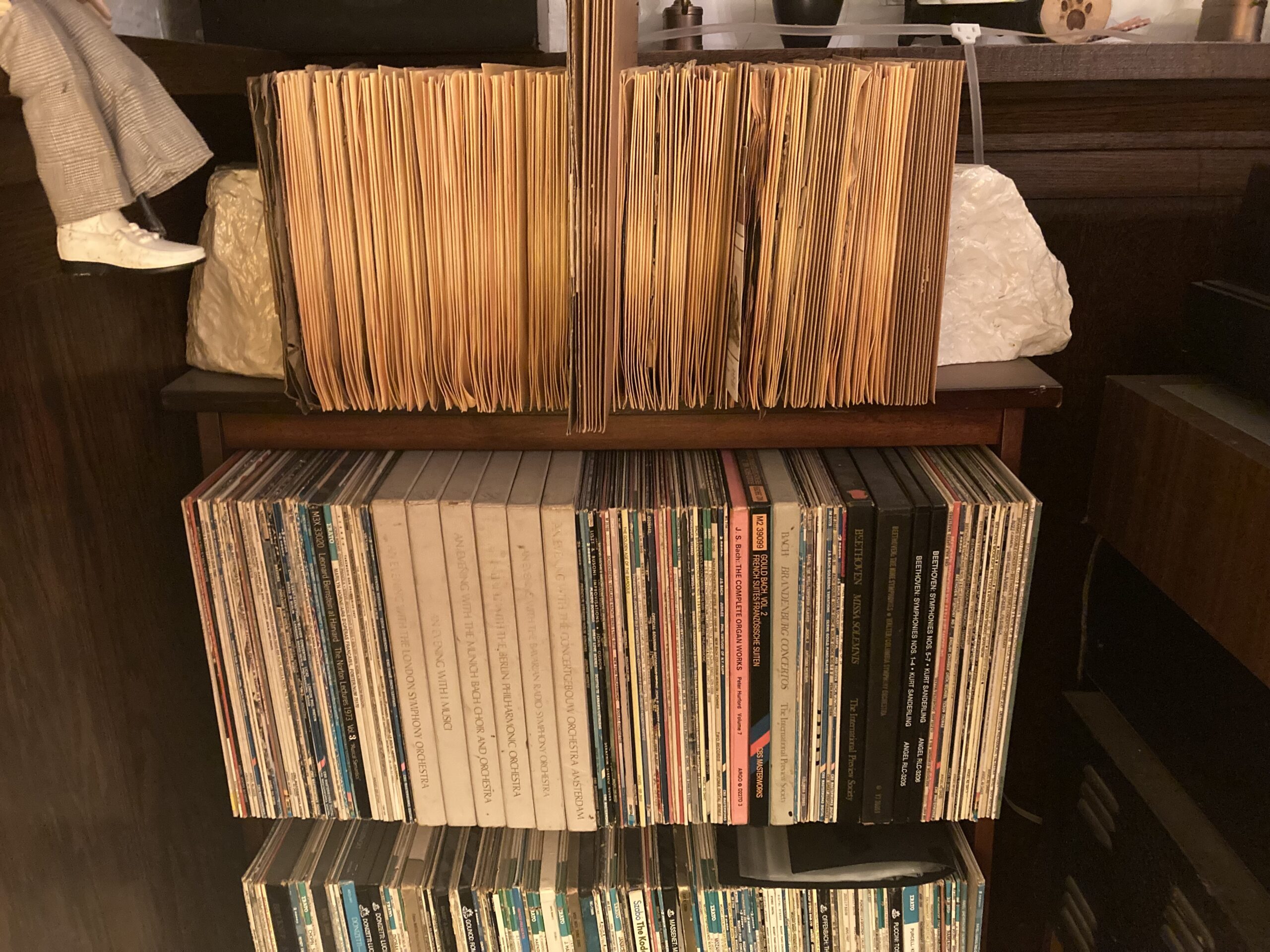

Bit by bit, then, I began to think of my collections, gather them about me, and ultimately, to think of myself as a collector. When I got a gig capable of supporting my various whims, I began digging into my predilections in earnest. In 2004, I bought an Edison cylinder phonograph from Tim Fabrizio. It came with an assortment of records, and I set about collecting more. I discovered Nauck’s Vintage Records and his bi-annual auctions, and that became a source, not just of cylinders, aka ‘wax,’ but also ‘shellac.’ And all the while, I had gotten back from the childhood home, and other remote locations, my collection of vinyl.

For a long while, these records lived in boxes. It was eventually, because of moves hither, a curated, alphabetically organized collection. At some point, before the collection was organized and moved hither, it was the victim of a flood. In the ’80s, I had moved back to my parents house. That house, on Moffet Road in Silver Spring, had a drainage problem. One fine evening, as I danced the Contras and Squares at Glen Echo’s Spanish Ballroom on the banks of the Potomac, the rains came down hard. Cars swirled in the Ballroom parking lot, though not my shitbox AMC Hornet. Back home, at 1612, the basement flooded. My collection took a bath. The favorites, in a pile near the audio gear, took the worst hit. Confronted with the muddy mess, I took a stab at cleaning a few of them, but, ultimately, most were lost causes, the covers ruined and moldy, the vinyl caked with that damned red-brown Maryland mud.

In my Kansas City days, I had a ‘straight job’ working the floor (and occasionally writing for the Pitch) at Hal Brody’s Pennylane Records. This gig provided an endless stream of vinyl. It was positioned in time right at the birth of digital media, and though we didn’t know it yet, vinyl was poised to become a nostalgia item. Fast forward. The contents of the boxes eventually emerged onto shelves once I owned a house, beginning in 2007, and could “manage the way I lived.” I also began augmenting the collection with finds on trips to junk shops. With the records now on shelves, they began again to be regularly played. The AR-XA gave way to various turntables and changers.

It’s time to think now about the gist argument. Re: collections… 1. The enjoyment of the sound (music, whatever) embodied in the recording is the key to owning such media. 2. It’s a dirty world, and nothing lasts forever. 3. You can’t take it with you. Then there’s the corollary: somebody is going to have to eventually deal with it.

Now that we’re oriented, let’s dispose of some foolishness. Record changers, difficult to maintain and keep operating, are not bad, evil, or instruments of vinyl (or shellac) destruction. If one is going to actually play records, destruction is going to happen anyway. Gradually. See above. Take a deep breath. You can’t take it with you. Someone (else) is going to ultimately deal; inherit what you have done whatever with. The thing is, though, in the here and now, dirt sounds bad. Vinyl, particularly, is static prone, and static is a dirt magnet. So if we’re going to manage our enjoyment, we have to manage the dirt. Changers do indeed compound the dirt problem. So record cleaning is important. How important is a matter of how much noise you want to deal with, and how far you are willing to go by way of dirt management. Another important thing to consider: not all records are valuable. Some are junk. This is not to say they are not worth collecting or playing. On the contrary. One’s enjoyment is not limited to ‘value.’ Value, in the monetary sense involves two factors. First is rarity, and second is desirability. These factors interact to produce market values, which sometimes become very inflated. Sometimes the rarity produces the effect of desirability. Sometimes, as is often the case with valueless junk records, the desirability is entirely in one’s own mind. Rarity, though, is a much more empirically evaluated factor. “There are only 50!” “There is only ONE, and this is the ONE.” Better clean it before you play it. Don’t play it too often. Make sure your equipment is in good condition before you play it. OTOH, if you never play it, why own it?

So then. The records I own fit into all of these categories, and are subject to all of these considerations, and I have made every possible mistake with them, and broken every damned one of these ‘rules.’ So there. I’ve said it. Let’s get to work.

If the record is not too dirty, we’d better not do too much to clean it up. The best method is the brush.

My technique with the brush: I put the record on the mat, start the platter, and apply the brush. The brush won’t cover the whole 12 inch disc. I do one segment, take the brush away, and wipe it. You can see that this particular brush has a tray that has a cleaning felt at one end. I use that. Sometimes, in the heat of the moment, I clean the brush with the side of my hand. Yes, bodily fluids are now contaminating the brush. But the dry brush itself is generating static. I don’t use liquids on the brush. Every time I’ve tried using some anti-static cleaning fluid on the brush, it just drives the noisy dirt deeper into the groove where I don’t want it. So I use a dry brush, and clean it between applications, and do this until the brush comes off the spinning record clean.

Notes: you can’t do anything about scratches or gouges with a brush. You can’t fix this kind of broken. Warps also cannot be fixed. Cracks add the danger of stylus destruction, but sometimes a cracked record can be played. It would be smart to play it once and capture it on digital or analog media. I can’t say I always do the smart thing. It all depends on who badly I want to hear the material, how much I value the record, and how much I think it’s worth.

Sometimes, though, you can see at a glance that the brush won’t work. If the dirt is really caked on, or if it’s mud or worse, grease (like finger oil), or, you know, a glob of, say, jelly doughnut, the brush is just going to become itself fouled, will merely spread the dirt around, and in general, be useless. In this case, it’s time for the dip.

The idea of giving a record a bath can be accomplished in various ways. This one, using the Spin Clean, which is still available on Amazon and elsewhere, is one of the most “cost effective.” Here’s a rundown of such systems, with the Spin Clean where it belongs; at the bottom of an escalating heap. Obviously, I have not tried the more and much more expensive systems; my philosophy argues against it. A person who is going to pop three grand (!) for a record cleaner is not going to be stacking records on a changer. No, no, no. That person will not be an ‘audio cheapskate.’ That person will own a turntable like one of these. That person will be getting up off the couch (or floor… or beanbag chair) to play each and every slab of pristine sonic goodness manually. I have a mixture of pity and envy for these people. The scale might tip a little towards envy. I could use the exercise, and I want the music (audio) and not the noise. But on the pity side, there is no peace in this world for purists, nor, for that matter, those with ‘perfect pitch.’

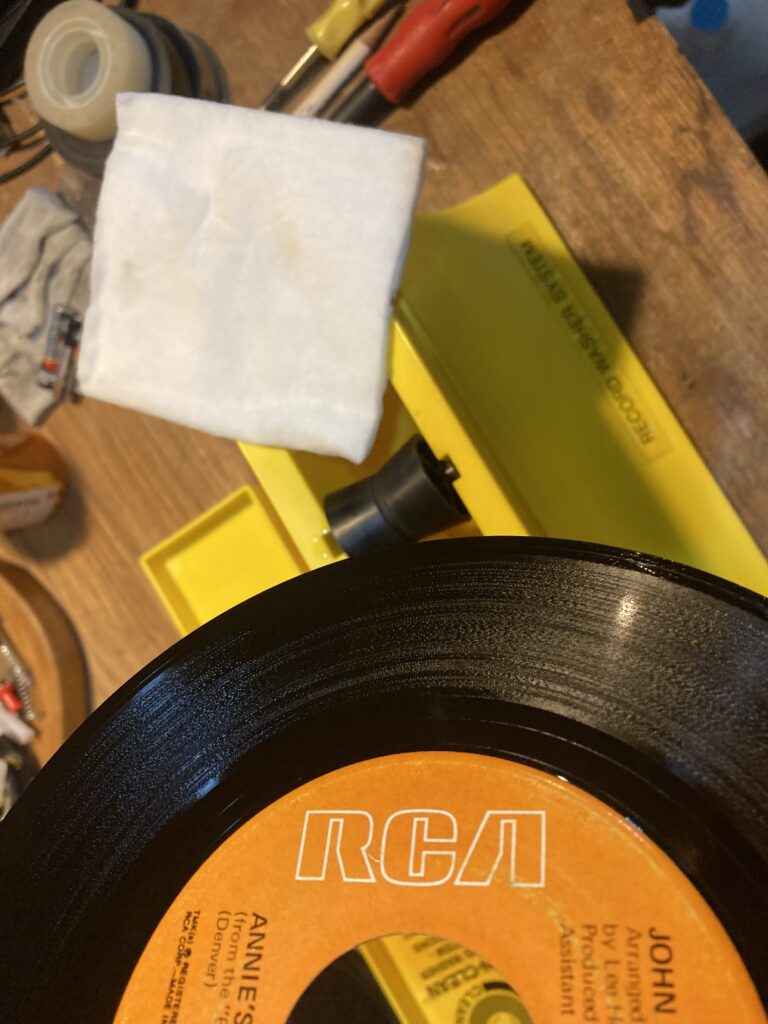

Let’s look closer at the Spin Clean/ ‘dip’ method:

Here, the Spin Clean is set up for 7 inch records. The pads can be removed. Onto the pads, the sauce is poured. Three or four capfuls of whatever it is Spin Clean is selling, or it could be something like this, as recommended in a discussion on Discogs:

800ml Distilled & De-Ionised Water

200ml Pure (99.9%) Isopropyl Alcohol

5ml Ilford Ifotol***

*** = Ilford Ilfotol Wetting Agent.

Uh… you might use any of the available record washers out there. If you’ve already bought into my notion that you can’t take it with you, you’re going to stack these on a changer, and you want to get to enjoying your audio right now, before it’s too late, then it won’t matter much as long as it’s wet. Some dish soap might do the trick, but I wouldn’t overdo it.

So once you have the tub filled up to the line, the record goes between the pads and rests on the rollers. There’s a trick to keeping the record in the rollers. A little downward pressure, and rotation are the keys. Nitril gloves might be handy, but I don’t usually use them. I’m careful not to touch the groove with my fingers. Otherwise, we’re just making things worse, eh?

The wet record then comes out and must be dried from the soaking wet condition. I use Webril wipes, but the idea is to use a lint free cloth. Spin Clean sells a rag, which can be laundered and reused. The problem with the Webril wipes is that they become saturated and dirty and must be discarded. I get through no more than 3 to 5 discs with a wipe. I usually use two; one for a first pass to get the excess fluid off the record, and one to get it drier than that.

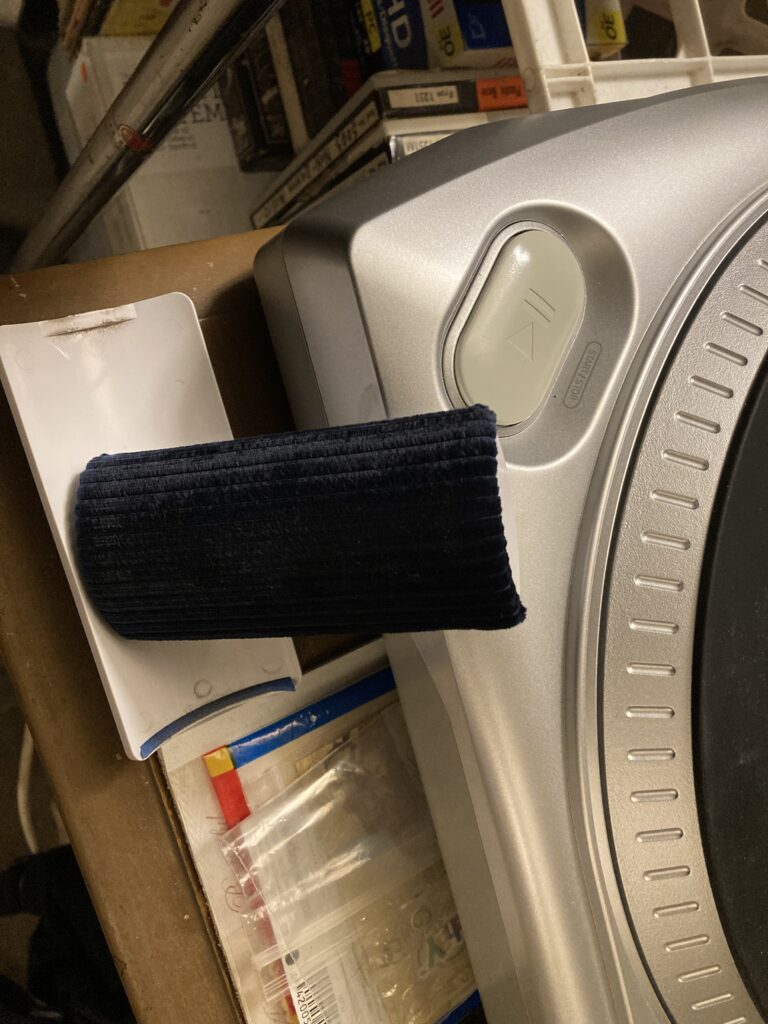

Then, I hang the records up on a rack to air dry the rest of the way:

Obviously, this particular improvisation works for large center hole records. You get the idea, I’m hoping.

Once dry, the records can be brushed and played.

All of this is not to diminish or disparage other methods. If I were able, I’m sure I’d have that fancy cleaner, and even fancier turntable. Pretty sure I’d still be playing them on a changer now and then, though. Love my antique audio.

but you are my baby

Damn the vinyl you have played is amazing I love you man.

Love it. Particularly the photos.

Ken – It is a good thing we kept records that we started collecting in the 70’s. The popularity of vinyl in recent years has made the price of new and used disks increase dramatically. Keeping them clean certainly adds to the enjoyment – esp. for solo/small group jazz with lots of quiet passages. I, too, can’t justify spending a lot on the fancy cleaning machines – I’d rather spend that money on more disks. Thanks for the tip on the lint-free pads – I just ordered some to try out.

Webril wipes aren’t perfect. But I’ve used ’em dry on wax and shellac with good results.

BTW, I played a piece of tape I made from one of your records back in the day… the Overture from Tannhauser. Was it Solti conducting? I don’t remember. But that is a superb record, and the tape still plays just great.