As usual, I have more questions than answers in trying to document this project, which took place in August and September of 1982. Then, there was the spinoff project, which sprawled into the late 80s and maybe even the early 90s and beyond. And by revisiting all of this, it becomes imperfectly circular.

Here is a rough guide to the territory I’d like to cover in this documentation well after the fact:

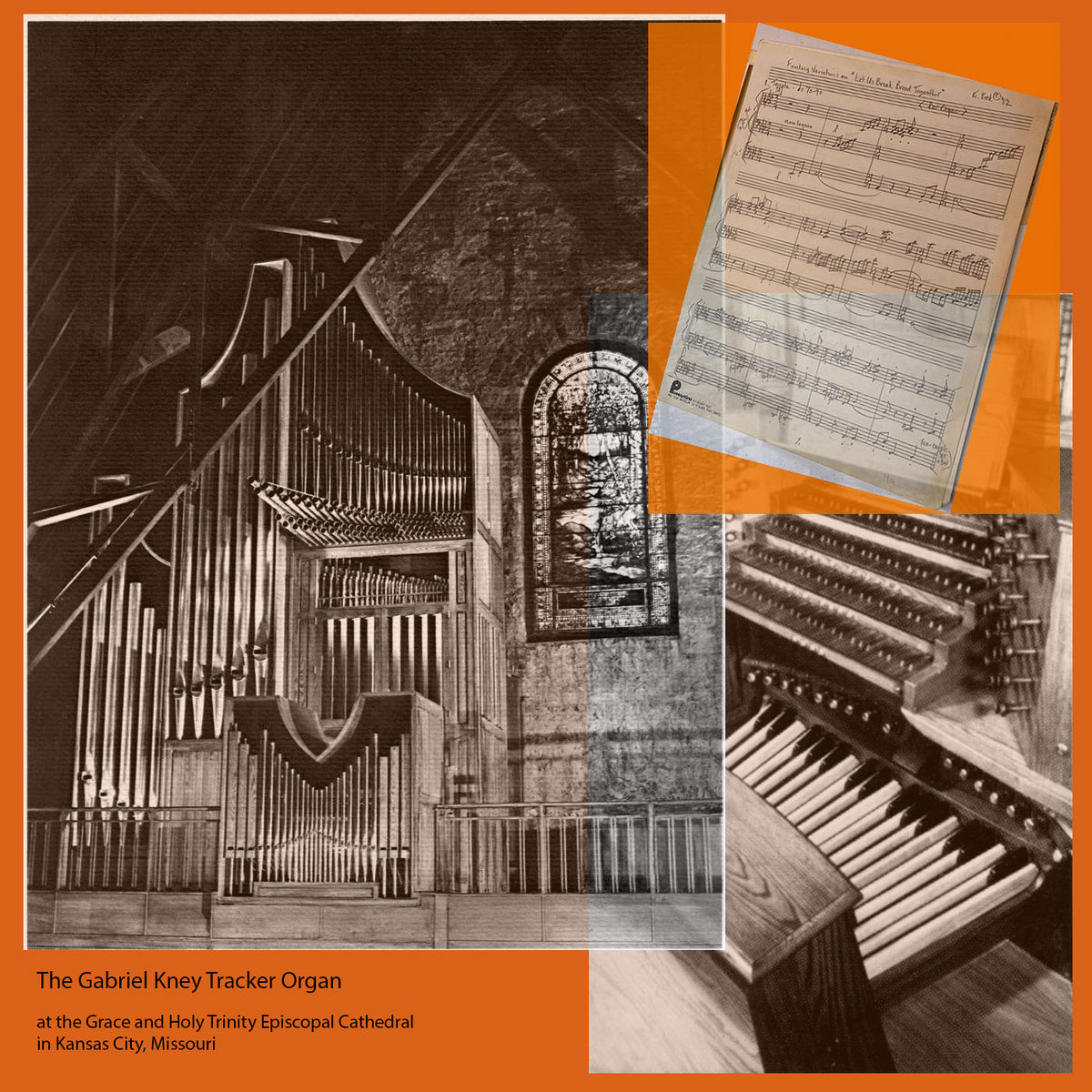

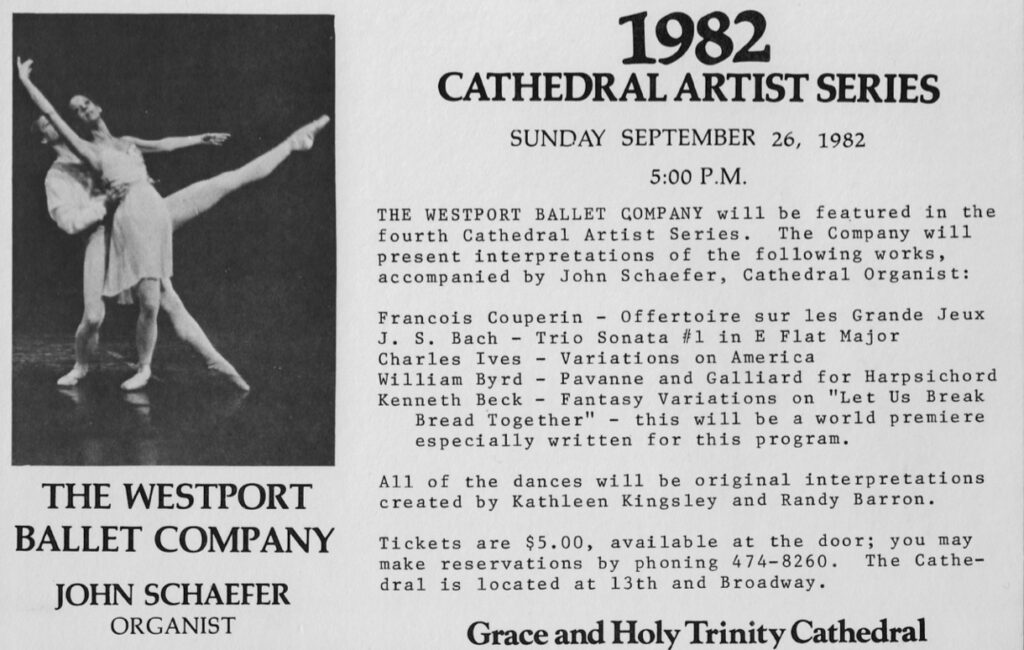

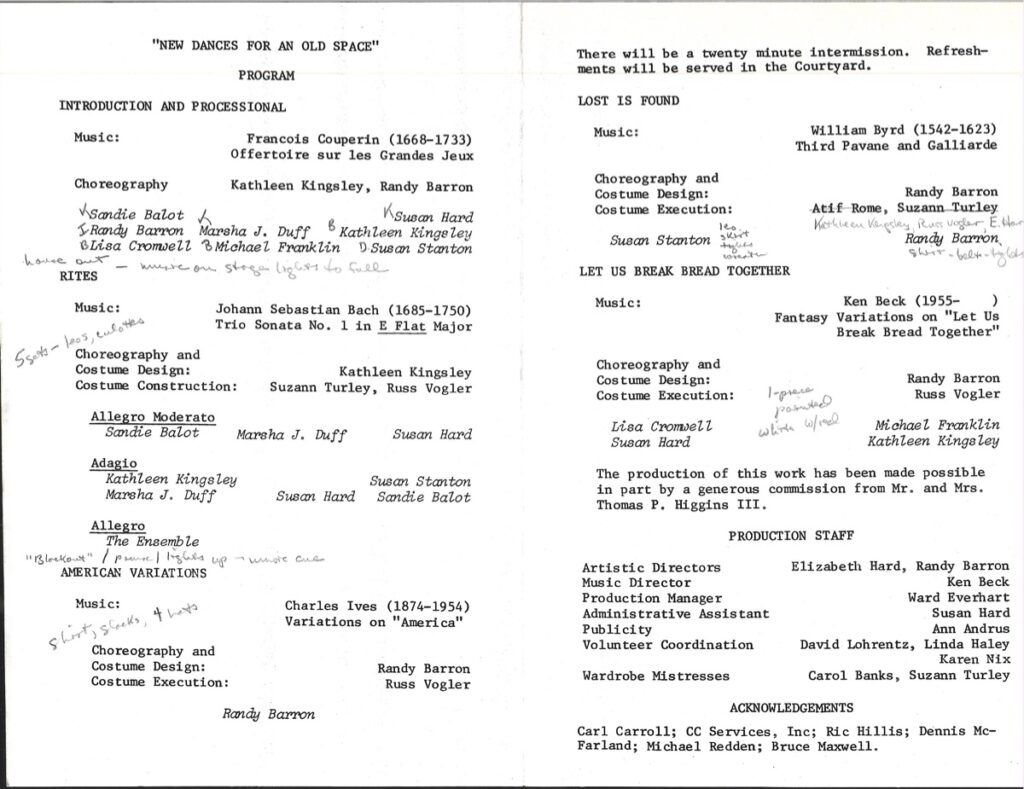

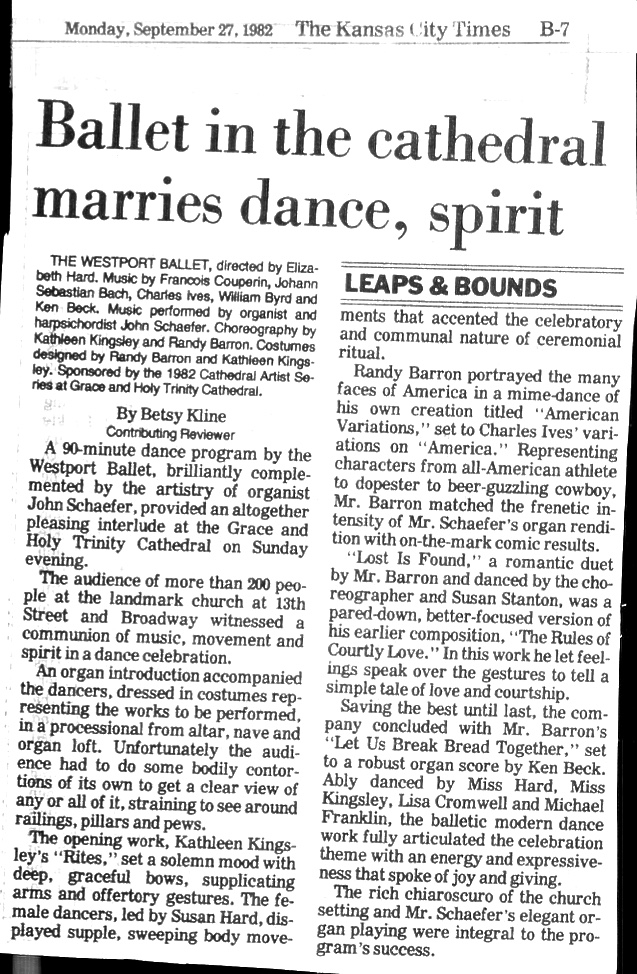

In 1982, the Westport Ballet Company of Kansas City, Missouri, was signed up to dance as part of the inaugural concert celebrating the new installation of a Gabriel Kney pipe organ in the Grace and Holy Trinity Episcopal Cathedral, also in KCMO. The organ had been installed in 1981, and there may well have been other events that related to the installation. It was, I gather a big deal for the church, if not the city in general. It was of great interest to me because I’d grown up in churches back east, in the Washington DC Metropolitan area, and then had run into organs and organ students, with a side helping of teachers and practitioners of the organ-playing arts as a student in Boston. My student days were not far behind me in 1982. I had graduated in 1977. The Westport Ballet gig was my second real dance gig, and my first one, at the Ballet Sioux (aka, the Siouxland Civic Dance Association), in Sioux City, Iowa, had been only marginally real. I had been only marginally competent, and only very dimly aware of the role of the musician in the company and service of dancers and dance. So the opportunity to write for a church gig for real, with an actual performer other than myself willing to play the piece, was a most welcome project. Only a callow youth such as myself could take such a gift in monumental stride. But I did it, and I did.

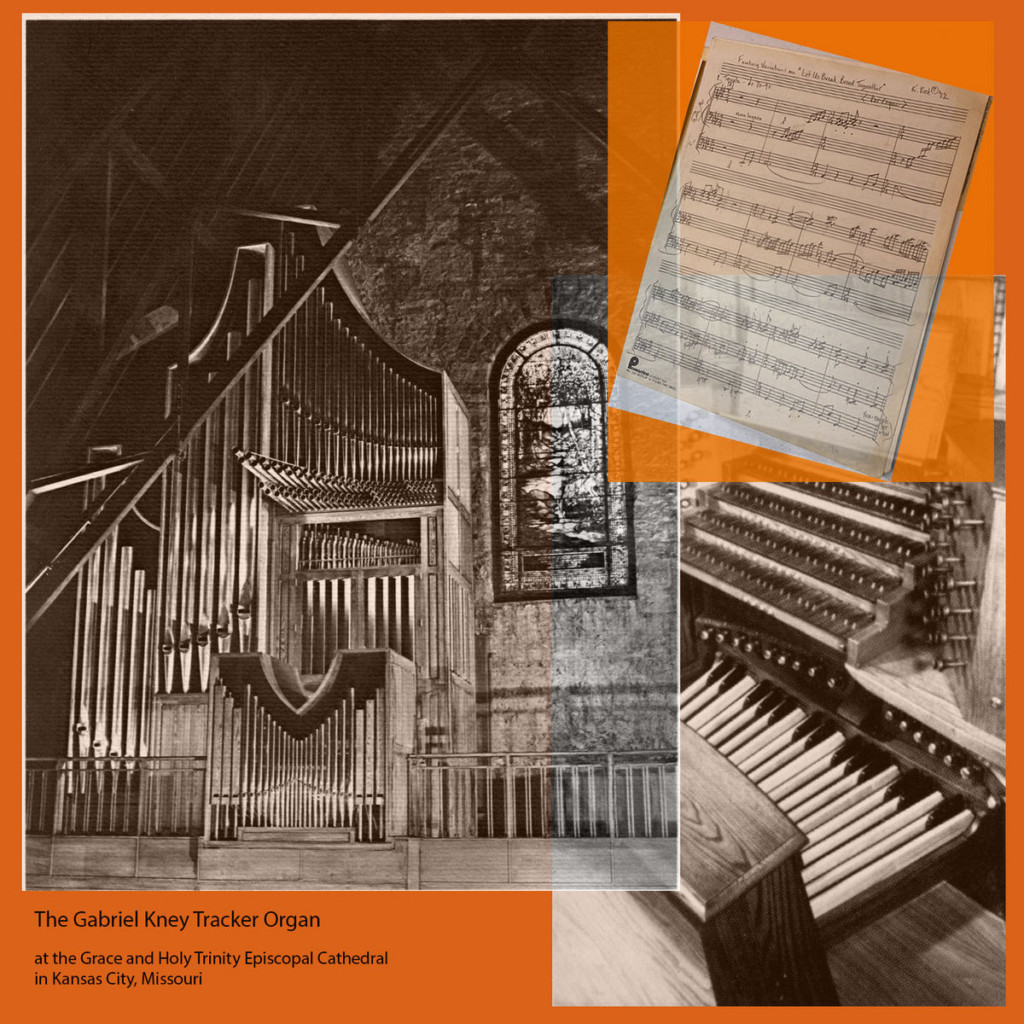

Also, astonishingly, there is no word in my journal about this piece. Much is written there about my pursuit of the unfair sex. I seem to have painted myself as what we would now call an incel, but that cannot be accurate. I was voluntarily difficult and standoffish, but I digress. So the paper trail for the work that has the title “Fantasy Variations on ‘Let Us Break Bread Together On Our Knees'” consists of a pencil score and a copyright notice. The audio record is a bit better. There are several spools of quarter inch tape, all recorded at 7 1/2 inches per second, and all in the quarter track stereo format. I had a Pioneer RT-701 at that time, and a pair of AKG omni-directional microphones, and these were hauled down to the sanctuary. I’m sure I did no climbing and placed my mics down in the sanctuary facing the pipes. I edited the takes into a performance master for later performances by the company, and must’ve made dubs, because splice free dubs exist. I recorded a dress rehearsal, which exists splice free. I’m not sure about the timing of all of these sessions and events, but the resulting piece is, in my opinion, quite well made and a solid example of my composing in the wake of a good conservatory education, with a good understanding of pipe organs and organists

The organist, in this case, was the organist/music director at Grace and Holy Trinity, John Schaefer. I have a memory, once the gig was on the calendar, of going down to a first meeting with John at the church with choreographer Randall Barron doing the driving. I did not have an automobile in Kansas City. As I recall, John met us outside, and led us in. John Schaefer was the ideal collaborator. As a young composer, I did not realize at the time how rare and valuable that is. He was an excellent musician, and gave much to the project, both at the time, and as it turned out, over the years. Schaefer led me up to the organ loft to look at the console, while Randy went down to the sanctuary to check out the lay of the land. I recall getting a pretty good look and listen to the various features of the Kney tracker. Its most spectacular feature was a rank of fanfare pipes, which had a marvelous, nasty biting sound. I vowed to make good use of that. Schaefer said he wasn’t good at parallel thirds. I stayed away from that and wrote straight up conservatory counterpoint. It cannot be stressed enough: this simple exchange of information, this meeting with the performer and viewing and hearing of the instrument, was, unfortunately the exception rather than the rule, and it made this particular piece all the more effective for its purpose.

In retrospect, the purpose, ie., as a choreographic-composition collaboration, is almost unique in my experience as a dance musician. I wrote the piece for John. John recorded it, and Randy choreographed the result. This is a very rare process, as it turns out. I’ll bet that this is the method many composers who think of writing for dance imagine. But it is upside down compared to the norms. More usually, the dance-music collaboration is a matter of satisfying the requirements of an existing (or farther along) choreographic vision, and finding a way of supporting and enhancing the resulting theatrical event. I was spoiled rotten by this experience right off the starting block, and had been since Huckleberry Finn went up at Jackstraws Courtyard. There’s another group of pieces that needs to be rescued from oblivion. But I again digress.

I remember very little of the event, and nothing of the choreography. I feel some shame about this. What I do remember was that after a very fine dress rehearsal, the piece went south in the performance. At the ‘big finish’ that ends the piece, where apparently a toe stud kick brings in the full organ, John kicked and missed. Thus, in the performance, the piece ended not with a bang, but a whimper. I recall that John felt so bad about this mishap, that he wouldn’t come down from the loft, and, if I recall properly, began the finale again as the audience filed out. I seem to remember going up to the loft and speaking with him in his misery. I was not all that upset; I had, after all, gotten my piece in the can and public performances to tape would follow, and the church gig was what it was/had been.

Unique among my pieces, this one kept the loyalty of the performer. John played the piece periodically, and over many years. One result was the ‘spinoff,’ which remains undocumented to my knowledge. Apparently, a member of the Grace and Holy Trinity congregation, Ms. Cynthia Schwab, had a brother in New York, William Herrman. She got the idea to commission a piece as a gift to him based on one of his favorite pieces of church music. That piece was by Leopold Stokowski, who had begun his career as an organist in New York. (Composer Virgil Thomson had the Trinity gig as an organist back in the day. He googles that to make sure it’s not misremembered BS… But, again and again, I digress.) Stoke’s piece was called Benedicite Omnia Opera, and it is performed here on youtube, interestingly enough, around the time I began working on the commission. My instructions were “old wine in new skin.” The result was another organ score, which I called Fanfare and Fugue on a Theme by Stokowski. I made the piece, and began making a documentary recording on four channel tape, with a two channel mix. In the midst of mixing, I was visited by Wendy Crockett, of Native American Spirituality fame, who had some choice, unkind words to say about the piece. “What is this? It sounds like the IRS is coming after you or something!” I quit mixing, and let the New York performance ahead be ‘the thing.’ Except that it wasn’t much of a thing at all. I went to New York from DC, stayed with friends, and we all went downtown to the big church where the famous organist butchered my piece, leaving much of it out, and improvising his way through what he did play. My friends asked me afterwards if I wanted to hang out, and maybe go up to the organ loft and meet the organist. I declined. My face was still burning. I suggested that we go get some lunch. My interest in the Trinity organ project faded, and it has taken all this time to get back to working with these recordings.

Here’s a postscript:

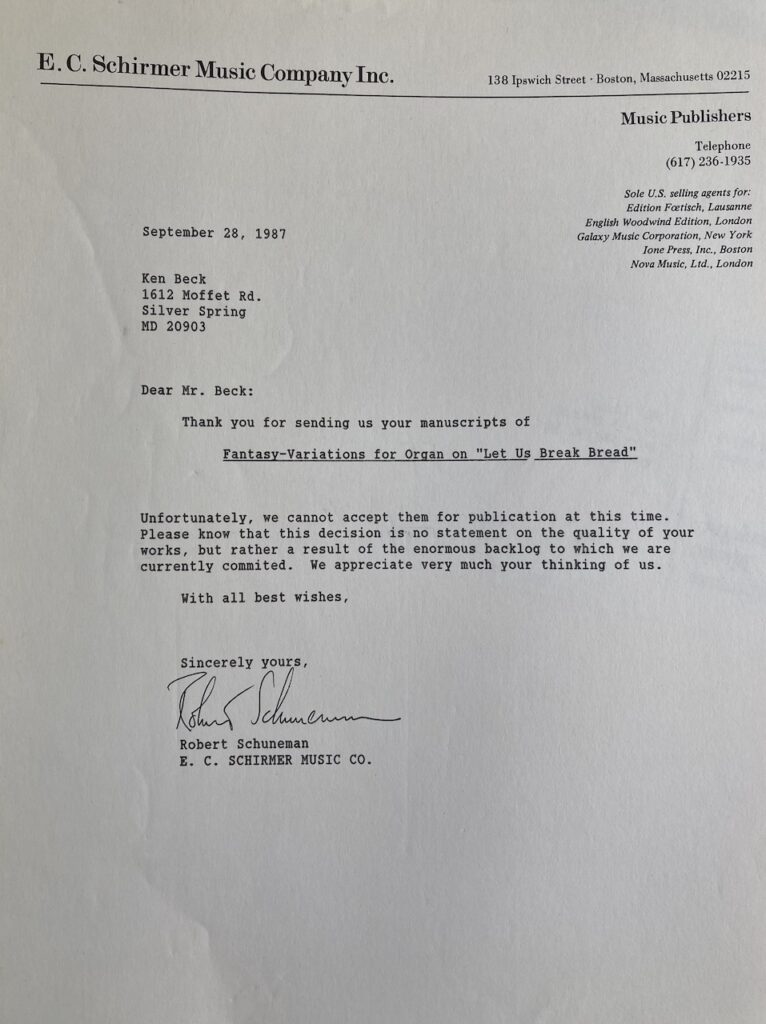

As I mentioned above, Schaefer continued to play these pieces long after the dance performance at Grace and Holy Trinity. He corresponded at one point, asking for a score for the Schwab piece. At that time, I looked at it and perhaps listened, though, as I got older and more deaf, the two acts were mixed and mingled, superfluous to one another, with reading the score usually winning out as a means to get the sounds in my head. I found a place in the Fanfare and Fugue where I thought the drama might be enhanced by the addition of a few more bars; more time. I did this, and sent the amended score along to John. I never did make another attempt to make a realization, and, therefore, once again, documentation falls short here. Schaefer also advised me in a letter to publish. I sent the Fanstasy-Variations score to E. C. Schirmer in Boston. I ran across their rejection letter in hunting the score for Fantasy Variations down:

Another postscript, re: Cynthia Schwab…

I made email contact with Ms. Schwab. She tells me that the Fanfare and Fugue have been performed at both The Church of the Heavenly Rest, at 1085 5th Ave, New York, NY, as well as The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, at 1047 Amsterdam Ave, New York, NY. Heavenly Rest was Herrman’s home church. A quick bit of googling and one gets to his obit in the Times. The obit tells of William’s deep involvement in things Episcopal in NYC. A phone call with the 91 year old Cynthia answered a few questions. The St. John’s performance was about five years ago, on the occasion of Mr. Herrman’s 80th birthday. She said the performance took place after a service, rather than as part of one. Cynthia was unsure if recordings of any of these performances exist, wished I’d called earlier when her brother was still alive, and remarked that he ‘saved everything.’ Perhaps the way to proceed is to contact Kent Tritle, the organist and music director at St. John’s. No harm there, I suppose. I, of course, am absolutely delighted that my piece was enjoyed by the commissioner and the recipient. Perhaps that’s where the matter can be, uh, laid to rest.