In a previous post, I was observed going through the KC journals and beyond looking for clues to the tapes and the resulting files. Not much in there about about process, and very little about dates of composition. Oh, there’s plenty about the other sort of dates, that eternal quest of the young male for female companionship. Such confessions we used to quaintly admit to at the time, often with a certain mixture of pride along with the anguish. So, the ‘bad songs’ are occasionally present as draft lyrics in the journal, but there’s nothing much solid to go on. I have to do my own archaeology.

I heard the Grateful Dead play at Memorial Hall in downtown Kansas City. I remember waiting in a line overnight, marking territory with sleeping bags, to get the tickets. That was alleged to be part of the experience. Indeed, it was. But the performance blew me away in the specific sense that it warped my head as to what it meant to be a composer. “What the hell was I doing?” I had gotten hung up on a dated model. The current way to reach an audience was by writing songs. That proved MUCH harder than it seemed at first. I had NO IDEA how to even proceed. That did not stop me. And in short order, I had a ready venue for my efforts in the form of the Black Crack Revue, Reverend Dwight Frizzell’s rag-tag ensemble of Art Institute students and hangers on. Even my stupidest, earliest efforts got a loving hearing in front of an audience. I learned fast, but I was slow to get involved in ‘what was charting,’ as the industry jargon had it then (and now). I was aware of what was charting, though, via my part time gig at Penny Lane Records. I was technically the classical records buyer, but I also took a shift at the front counter, the lifeblood of the retail record business. Of course, I also wrote occasionally for the ‘Pitch,’ owner Hal Brody’s ‘house organ.’ So between these several sources of knowledge, motivation, and opportunity, I was hard at it and aware how far off the mark I was. The mark was: the creation of a sellable, marketable ‘popular’ song. The popular part was critical, since that was the source of all commercial potential.

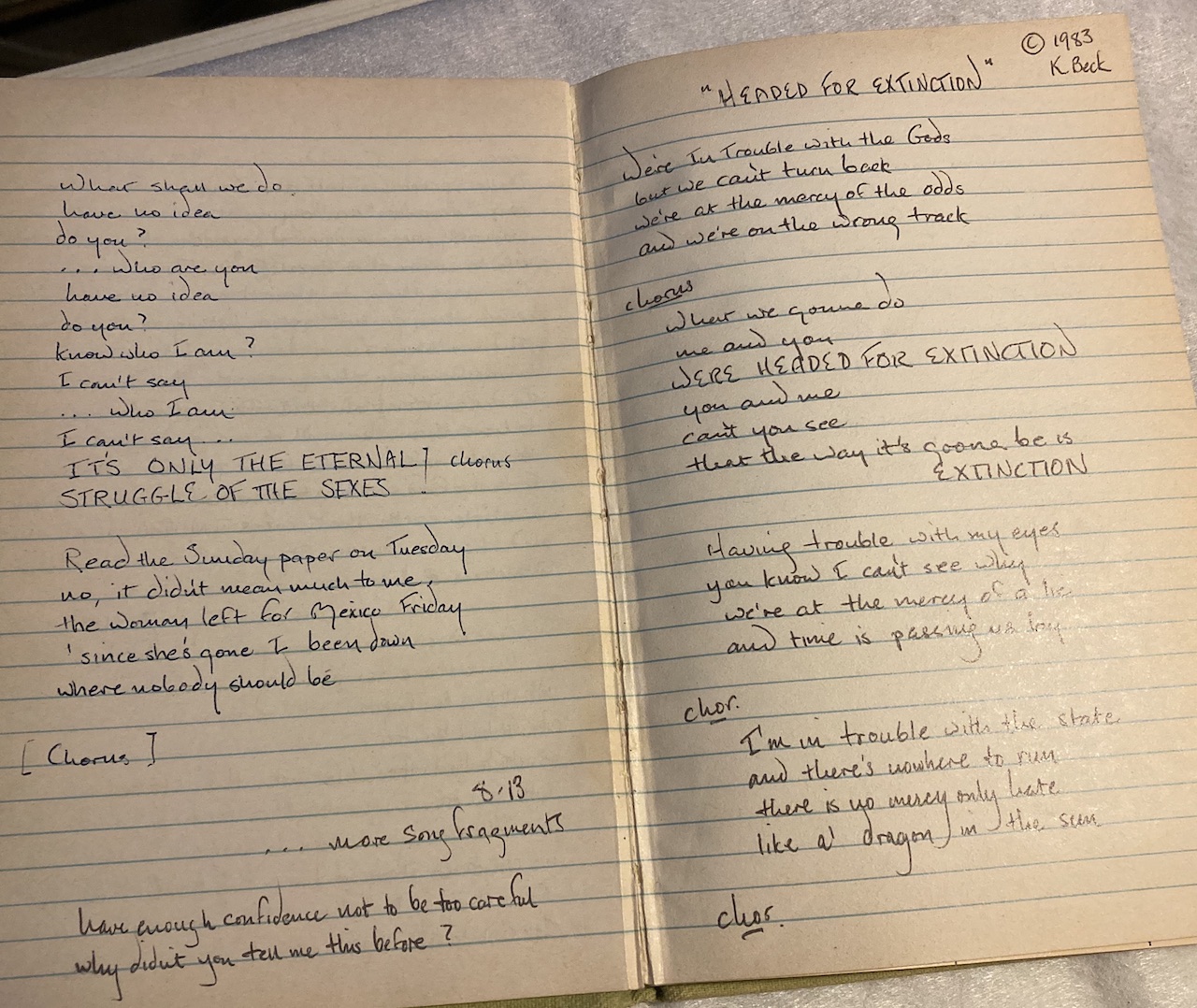

BCR was a fairly serviceable ‘big band;’ not that it was/is big in the way that C. Everett Longstreth, Boston Conservatory’s arranging teacher, knew or imagined. So instead of writing four way close for four horns and drop two for coupled brass, a more nimble approach was required. And the ‘bad songs’ got some pretty fancy treatment alongside the pieces made for the two or three various horns and rhythm session that was the Black Crack foundation. Most critically, the songs got an audience. They also got stage sets, and there were gigs for which songs were specifically composed. New Years Eve at (now closed) KC’s Harlings Upstairs resulted in Headed For Extinction. Did Valentines Day yield Saying Goodbye? Probably not. But the potential was there and aspired to. The most memorable theatrical BCR event from a production standpoint was the construction of a papier-mâché solar system (!) for one particular New Years Eve. We put on a good show. And the band, all these years later, with fresh and old blood mixed, is still going strong.

Early on, I had also encountered John Trubee and his song poem stunt. I’ve written about that here. I adopted the format: vocal on one channel, backing on the second channel. My first song, She’s Only Counter Culture After Five, was recorded in exactly this format on 1/4 track quarter inch stereo tape, at 7 1/2 ips. A copy of Trubee’s record follows it on the spool.

Somewhere in there, in 1984, Elton John came out with Sad Songs Say So Much. I instantly morphed it in my own way to be a justification for the material I did produce. As all artists must, I wrote what I was compelled by inspiration to write. I was trying to write good songs, and strong pieces, to the best of my youthful ability. It was clear that I was falling short of the mark, and the idea that even a bad song was expressive was seductive; perhaps there was an aesthetic there that held greater allure for me.

This, then, is as good a place as any for a discussion of what I mean by ‘bad songs.’ This is a bit like Harry Frankfurt trying to get at what is meant by ‘bullshit,’ or Aaron James work ” – On Assholes.” That is to say, there is an aesthetic involved that is not exactly the same as ‘incompetence.’ A good example of what I would call a ‘bad song’ that says so much is Merle Haggard’s Okie From Muskogee. I’ll admit, it is not the perfect example. But it is not exactly a novelty song. It is completely competent. It is readable as parody, but it is not necessarily intended as a parody. It might be said that eludes sincerity. See Leonard Bernstein’s Norton Lectures for more on the quality of sincerity. (And here’s even more on that!) But you can’t tell by the sound or the text if Merle means that he’s really proud to be an Okie. Does anybody believe that there was no marijuana on that bus? The man was an outlaw, after all. The Okie in the song is clean as the driven snow. Takes no trips on LSD. Has a respectable suburban haircut. Wouldn’t dream of burning a draftcard down on Mainstreet. But one can sort of Imagine Merle Haggard doing exactly that. He did time for stealing cars, for the love of Mike! But ‘Okie’ was a hit record. Bad songs more properly fly under the radar. My songs garnered a respectable folder of rejection letters. Of course, that is not a certain indicator either. There are plenty of hit records, besides ‘Okie,’ that I think of as ‘bad songs.’ They are not necessarily parodies, or intended to be funny. The more competent the performance, the worse they get. Another treasured example, and closer to the bone, perhaps, are the George Jones songs recorded for Musicor. There is/was an LP called Heartaches and Hangovers. I became familiar with this one as I toiled away at the front desk of Penny Lane. I took a promo copy home and taped it. One of the songs, Things Have Gone to Pieces, became the template archetype for a few of my ‘bad songs.’ A hasty analysis notes the following features: each verse mentions two silly things that have happened, and one major life crisis. Each get equal weight in the the music.

- somebody threw a baseball threw my window

- the arm fell off my favorite chair (again). — not the 1st time, so maybe fix it?

- the man called to repossess ‘my things.’ — if no payment by ’10.’

In the chorus, things come into better focus: all these bad things have happened since ‘you left me.’ Half right is as good it gets. But, also, nothing turns out half right. (So it seems.) Pocket money, accounted for: 2 nickels and a dime. ‘Holding to the pieces of dreams,’ the final line of the chorus, is good song worthy. Quite poignant. But after all of this out of focus silliness, are we going to be moved? Maybe. Bad songs say SO much!

Also speaking beautifully in the George Jones recording is Jones’ magnificent, melismatic performance. His delivery of each line is ‘sincere,’ and matchless in intensity. He might’ve been drunk. Almost a certainty.

It’s also worth considering Mister Moonlight, recorded by John Lennon and The Beatles and released on Beatles For Sale. As a bad song that says so much, it can be examined apart from an immersion in John Lennon, The Beatles, their various histories and motivations for doing this that or the other. (But if you want to immerse, I provide a link.) We can consider only the music and the lyrics for the right of inclusion in the pantheon of bad songs (that say so much). Let’s first of all establish that it is bad. Many hearsay reports, particularly from the programmable cd and streaming eras, testify that listeners to Beatles For Sale skipped over the track. Here’s a link to a discussion of the song on Quora. No guarantees that the link will be persistent, so if it breaks, I probably won’t fix it. The lyrics belong to a tradition of thought that ascribes consciousness and even agency to a phenomenon of nature. The personification of moonlight as an agent of seduction is a recipe for brewing up the essence of the bad song, and it is caught in the act of saying so much. Maybe, even, too much. Way too much. ‘Come again, please?’ I think the heart of the matter is that the narrator wants more of moonlight than moonlight can deliver. He also, whether aware or not, is conjuring up that lyric about the harvest moon, that dispels the darkness that frightens all good girls lest they might refrain from the outdoor spooning. In June. Naturally.

The track that Lennon and The Beatles were covering was a b side by Dr. Feelgood and the Interns, aka Piano Red, whose name was Roy Lee Johnson. Musically, it has a sort of a calypso vibe, and features a peculiar break in the rhythm that ultimately ends the song. Harmonically and melodically, it is a bit ordinary and bland. These are not the devastating features in a song, and can serve to underscore the textual content. This idea touches on why songs are so difficult to make, unless one is Paul McCartney: it is a three ring circus involving melody harmony and text. These elements are most certainly in a contest for the listeners attention; it is the balance between them that makes a great song more than the sum of the parts, sears the memory with that indelible impression. We are wading around in the near misses, where the impression made is all too fleeting, and the satisfaction elusive. In Mr. Moonlight, we have an example of a song that captured the attention of the Beatles at the Cavern Club, and in Hamburg, and featured in their stage act, and made it onto a desperate, cranked-out LP, a song which says so much and yet falls short. Any Beatles fan can testify to this. There are certainly some who defend it. I herewith make a point with it.

Thus spake Stückenbeck.

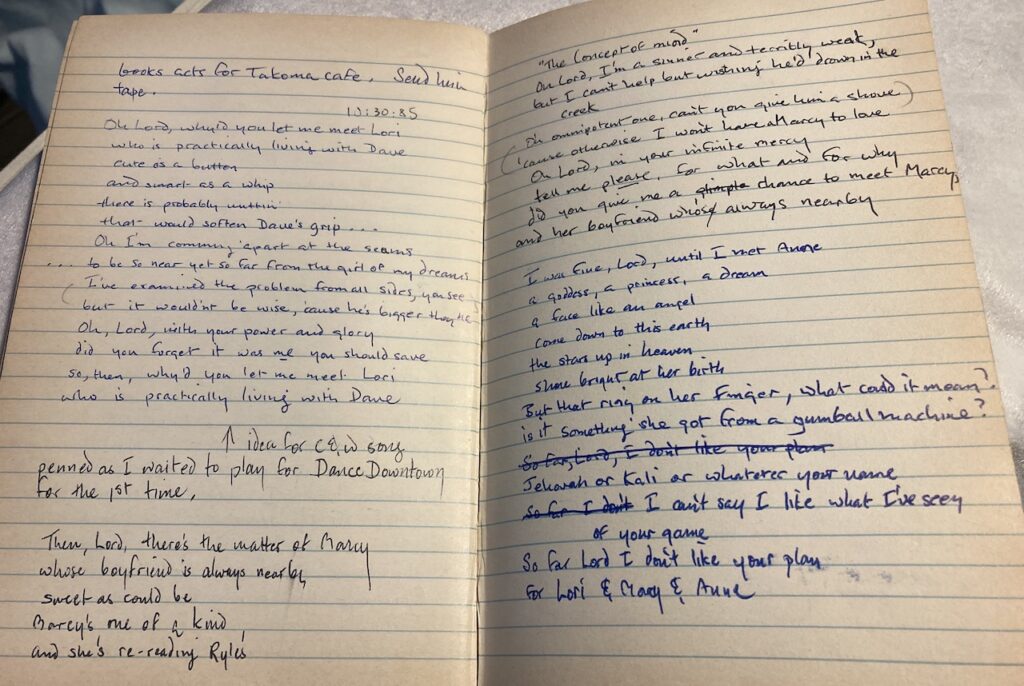

So I set about writing my songs, and gradually became aware of the aesthetic. I was never a vocal performer on the order of George Jones, or even, say, the MUCH lower bar to reach, Bob Dylan. I made a few bad songs with Dylan in mind. Lori, Marcy, and Anne, for example, features a Dylanesque vocal, with an imitation of Dylan’s famous approximation of pitch and nasty timbre.

In the meanwhile, I can think of a bunch more titles for this post, as I procrastinate the hard part: actually writing about the songs I’ve put up (or will have) on bandcamp. (Link goes here.)

So part 2 is called:

Essay Before An Upload

I’m thinking, of course, of Charles Ives. Though we’ll call him Chuck here, since that’s more appropriate for the song writing persona, and/or the ‘legion of Mikes,’ that amorphous blob of internetizens that hang out for rarities and every burp and fart by the greats. Ives called his essays Essays Before a Sonata, and the sonata was The Concord Sonata, that knotty, gnarly piano poem for the transcendentalists. But also, I’m thinking Ives because he self-published 114 Songs. Ives published also the Postface to 114 Songs, which is exactly what I am, in my own wry way, trying to do here.

You can follow the link for a selection of choice bits, but here’s one you won’t escape if you’re reading this:

Some have written a book for money; I have not. Some for fame; I have not. Some for love; I have not. Some for kindling; I have not. I have not written a book for any of these reasons or for all of them together. In fact, gentle borrower, I have not written a book at all–I have merely cleaned house. All that is left is out on the clothes line; but it’s good for man’s vanity to have the neighbors see him–on the clothes line.

Yep, Chuck, that’s it. I am merely ‘cleaning house.’ We don’t use clothes lines anymore. But you can see my dirty laundry here after the spin cycle and before the dryer.

I’ve already noted the start of the path with She’s Only Counter Culture After Five. I don’t think this song was ever performed with the BCR band. It instantly highlights the problems I had, and still have, with song writing: 1.) I have a hard time getting into the zeitgeist of ‘what’s charting,’ now or then. And 2.) I can’t sing. Not completely true: everyone can sing. You just open your mouth and make noise. But for the making of a successful commercial demo, a certain sound is requisite. I eventually was forced to admit defeat. It was a defeat that resulted from negative comments by listeners and the subsequent failure of confidence. I could re-tool and keep making songs, since I no longer care. But I also decided not to make songs (or poetry) unless I had an idea that would not let me “off the hook.” Many writers have noted this phenomenon. You get an idea, and it won’t let you rest until you ‘get it out of your system.’ This is the art that you are given by the muse or by fate. It takes nerves of steel to ignore such a prompt. And I don’t. To this moment.

But you can also make songs on demand, either personal or external. Planetary Blues was made for the BCR shows at Harlings in Kansas City, similar to the one noted above with the solar system piñata. The BCR shows were full of Dwight’s obsessions with dinosaurs and other creatures of times gone by, and I set out to fit in with my thoughts on environmental destruction, cosmic disasters, and extinction. Already noted: Headed For Extinction, but add to this group Suction From Space. ‘Suction‘ was often performed while wearing a lab coat. There should’ve been also a pointer and a chalkboard, since the song is a pseudo-lecture on black holes. I think this group makes the cream of the crop. These songs were performed to the best of my ability, and in some cases, have continued to be performed by the band in my absence. That does not make them any less bad.

Having started with She’s Only Counter Culture, a ‘relationship’ song, I continued in this vein with Saying Goodbye. Whereas the former was a weird sort of ragtime song, the latter is more of a ‘fake’ Country and Western thing. The Country charts are full of relationship songs, of course. Love songs of all types are the bedrock of songwriting, and there is always the potential that a meaningful, understandable, relatable, tale of seduction, attraction, love, and, usually, especially, loss will break forth from one’s pen under the heat of inspiration. I was too flippant, too insincere, and too snarky to pull it off. I did perform Saying Goodbye with the Black Crack Review. I painfully remember trying to get through the song, which I had played enough in take after take to have committed it shakily to memory, whist out on the dance floor below me, with saxophone in hand, the Reverend Dwight Frizzell yelling out comments at the end of each verse. This blew my mind, funny as it was, and I totally lost my place in the song. The performance went straight to hell, and I was pissed. Did I ever get through it? I don’t remember. I also recall this being one of those ‘won’t let you rest until you record it’ songs. I was hiking to my woman’s place in the KC snow, a good trek of several miles. The whole thing was done when I finally got there. The lady was out of town, and I was on place-minding duty. Her cats had to be looked in on, and the place monitored in general. I pushed the door open. The floor was covered with feathers. Because of the snow, I’d been slow getting to this chore. The cats, not willing to wait for me to show up with the kibble, had taken matters into their own, able claws. A few more birds had bitten the dust. So, you see, I wasn’t, in fact really doing anything the song tells of. It was a made up tale, just pure fiction. That’s the way of it, as it should be. It would have been great if the song were just a bit less… bad.

Headed For Extinction, by the way, was a pretty clever attempt to combine the two ideas: loss of a relationship, loss of everything else. My relationship was pretty solid, though. The human species, not so much. I still think so. The song is still relevant. Unfortunately.

I began doing gigs in the Kansas City metropolitan area public schools under the auspices of Meet the Composer. Two ‘bad songs’ were composed for this enterprise, A Gentle Feeling and Children’s Rights. Children’s Rights is the better of the two. I had forgotten about A Gentle Feeling until I started listening to tape. I am not sure I wrote the lyric. It is quite likely that the lyric was composed by the school children as a class assignment ahead of the Meet the Composer event. If this is true (I’ve got no journal entry to back me up, and I have not had the wherewithal to go through every scrap of paper on hand), it mirrors my absolute first ever experience with song writing. I had, in the fourth grade, (!) been involved in exactly this sort of class project. My class, under the guidance of Mrs. Peterson, who played the piano at school assemblies, had composed, as a group, a poem. It went like this:

Juicy Hamburgers on a bun, That’s my favorite dish, yum yum! Pickles and relish, so delish… etc.

I composed the tune and harmonized it in an afternoon and returned to class with it. The class was floored, astonished that I (or anyone they knew) could perform such a trick. It was my first brush with the humiliating notoriety that comes along with doing something easy, something so lame and cheesy as to be embarrassing, and, simply because of age or novelty, being excessively praised for it. The age part wore off, eventually. But the odd relationship with things people praise that one feels is unworthy persists. Bad songs, one way or another, say so much.

In any case, I clearly wrote and performed the music of A Gentle Feeling, giving it the four track treatment. Therefore, I include it in the group. It is not quite the kind of bad that I mean to celebrate. But there it is. Children’s Rights, on the other hand, was good enough to be performed by BCR. The recording included on bandcamp is one of me and Jeff Rendlen performing the song to my synth demo accompaniment. There are four channel recordings of the song as performed by the kids. I’ll include one of these takes eventually in the ‘every burp and fart’ category.

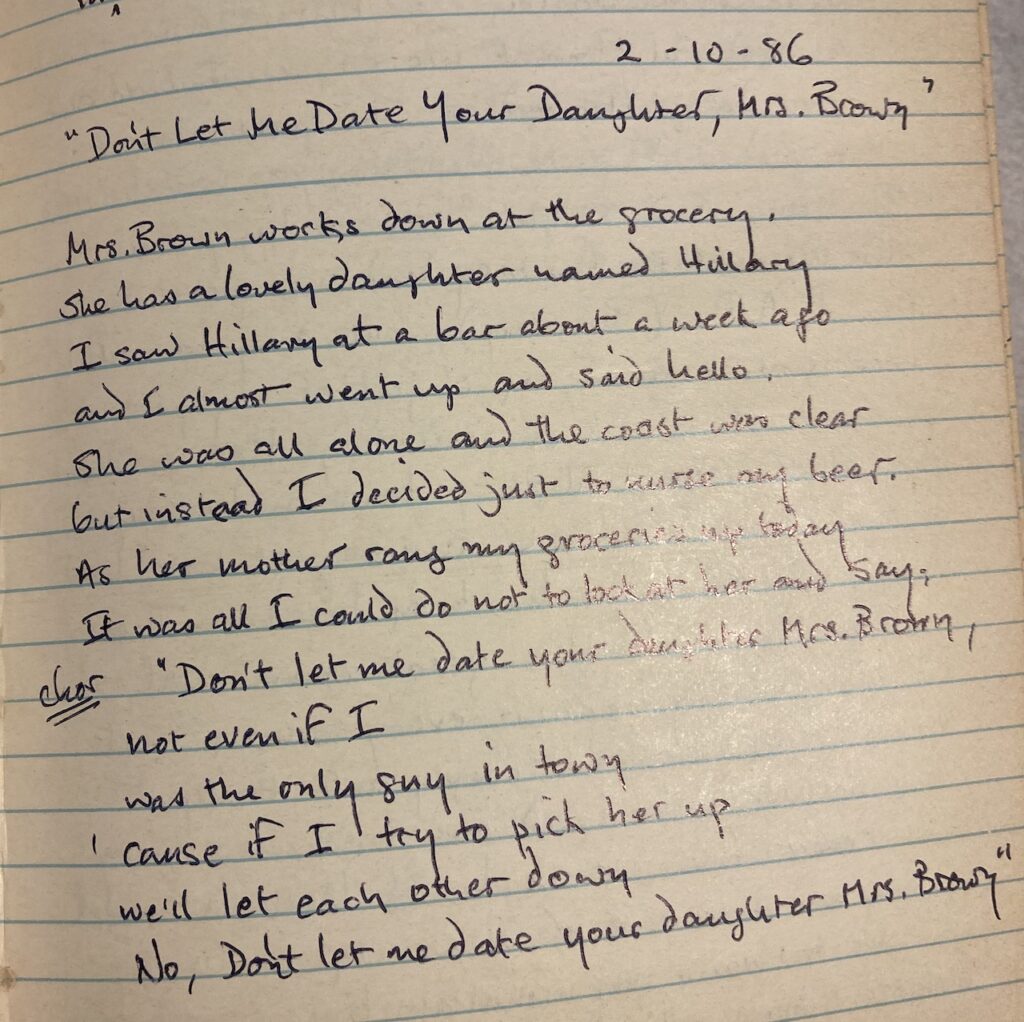

With Don’t Let Me Date Your Daughter, Mrs. Brown, I embarked on a sort of song-writing-as-therapy period, though I certainly wouldn’t have thought of it that way at the time. The time was 1985. I had had it with touring with the BCR. I had been sitting around my apartment at 301 E 43rd Street, listening to Brahms, particularly the 1st piano concerto, specifically that passage in the first movement at bar 157, and I was overcome with longing for my parents. I imagined them aging, and dying, while I farted around in the midwest being a musician. So, against all better advice, I decided to quit my gigs and move back to DC. The advice was correct, and it was rather a huge mistake, but it was a one way ticket and a non-recoverable error. I had to start all over in another, much less forgiving town. And my parents, as it turned out, lived another 35 years!

My mother was reading the Post as we sat in the family living room, Mom scouting for jobs for me, and perhaps also for entertainment. She read out loud a bit about the contradances going on down at the Spanish Ballroom at Glen Echo, the former amusement park on the Potomac, now closed, but being used for stuff, and having been taken over by the Park Service. Mary thought that might be fun. So we went down there. I was intrigued, but humiliated. Mary, I think, was just humiliated. She never did it again, but I did. Not only did it get me out of the house, but it also got me into the arms of an endless supply of single women. I also, slowly, learned to dance the squares and contras. Eventually, Mom found me an ad in the Post I could use: gig at the Maryland Youth Ballet. I went and auditioned, and was immediately hired. There was a certain amount of overlap in the cast of characters. Some of the adult dancers taking class at the Youth Ballet were also doing the squares and contras at the Spanish Ballroom. There were also dances of this sort going on up and down the coast; this had been going on since the advent of Englishmen on the continent. Americans had, over the years, modded it considerably, and continue to do so. At that point, Glen Echo was a madhouse, filled with at least four contra lines of considerable length. It was a furious scramble to grab a partner and get a dance. Once that was accomplished, one could line up the next dance whilst doing the current one. And it was good to be dancing, rather than accompanying. Callers and bands rotated around the circuit. I’m speaking past tense, of my past, but I assume this scene lives on.

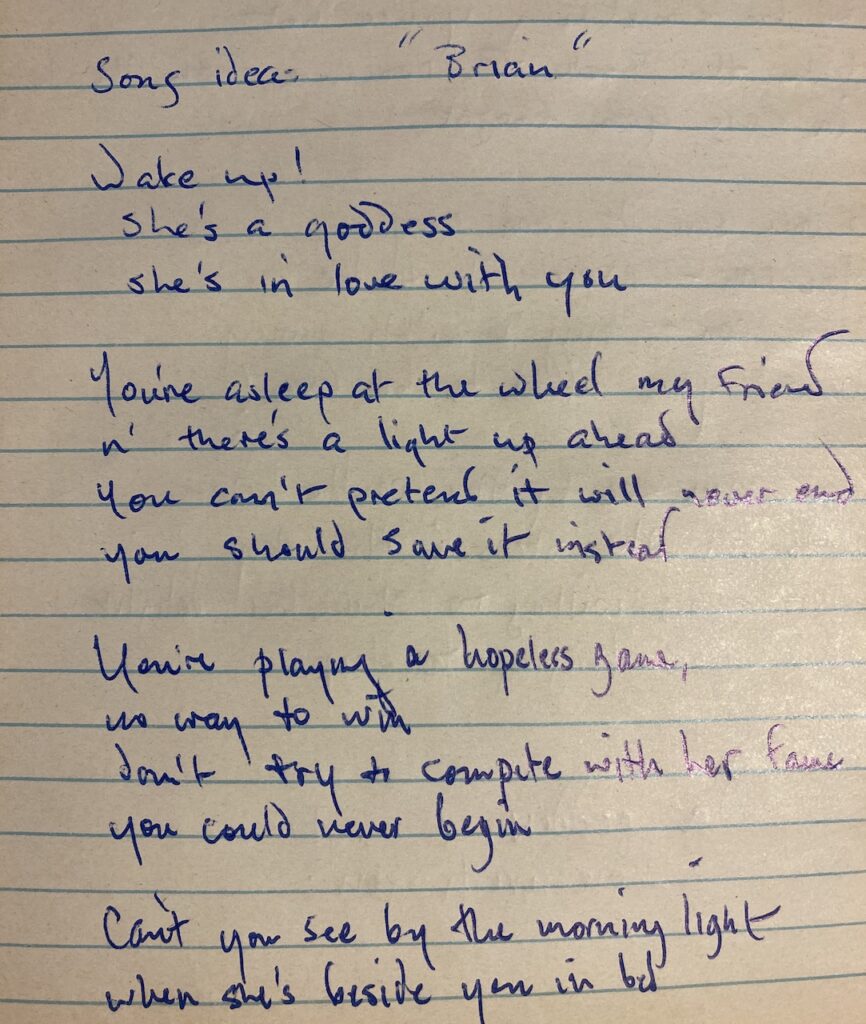

So, with so many women on my arm and available for fantasy, I had plenty of material and reason for songs. Lori, Marcy and Anne is a case in point. As noted above, I made it as a Dylan parody, though Dylan would have never been so ‘incel.’ Hot Little Number, too, is a bit more produced, but a perfectly cynical response to the experiences that began to pile up. Finally, Wild Bird reflects actual achy-breaky experience. The song is a bit embarrassing, but not nearly as embarrassing as things I actually did chasing the wild bird. I remained an incel. Until, of course, I wasn’t. Almost the moment I was in an actual relationship, I took a break from writing songs. Thus the gap between Wild Bird and Baby Talk. With Baby Talk, I had matured enough that I knew the following: I was never going to seduce anyone writing and singing songs. I was not much of a singer. My songs were not all that good. At best, they could be funny. I had developed an awareness that what I was doing was writing ‘bad songs.’ I was hanging out with people that reminded me that, indeed, my songs were ‘bad,’ if not, in fact terrible.

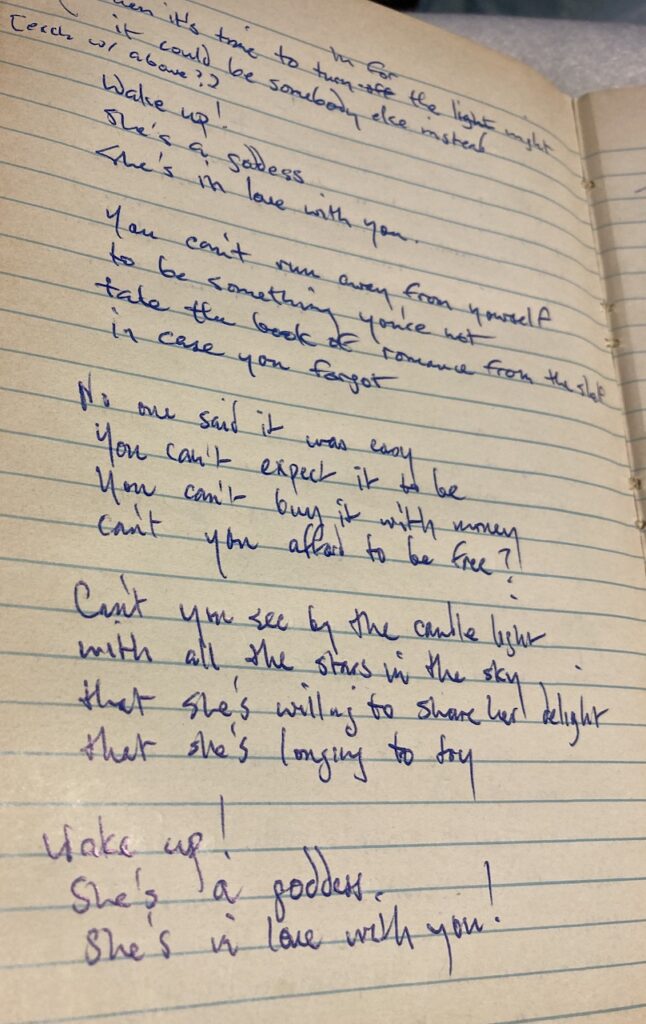

And, to sum up the relationship shuffle, I dated my way around the world. I married a German. I cheated on her with a Russian. I abandoned the Russian for an Israeli. I have never managed a good song, and I still am a clumsy folk dancer. As for the Russian, the relationship’s beginning, which marked the end of my marriage to the German, resulted in one last incel-style bad song. I made a demo, but never sang it. Thus, Dreaming is included in the group as an instrumental, with the melody played on a Yamaha PF80 patch. I had, for the time being, succumbed to the never-ending Washington DC area criticism of my singing. I’ll have to type up the lyrics.